Queen of Revolutionary Feelings

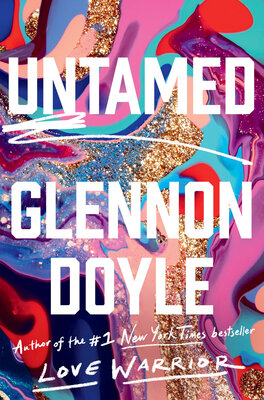

3/6/20 - She left her husband for a female Olympian. She survived addiction. And that's just the beginning. Glennon Doyle's new book Untamed encourages women to break out of being good daughters, mothers, partners and be good to ourselves -- and then, in living fuller lives, we can be better to our people and the world.

Transcript below.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Overcast | Pocket Casts | Spotify.

CREDITS

Producer: Gina Delvac

Hosts: Aminatou Sow & Ann Friedman

Theme song: Call Your Girlfriend by Robyn

Composer: Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs.

Associate Producer: Jordan Bailey

Visual Creative Director: Kenesha Sneed

Merch Director: Caroline Knowles

Editorial Assistant: Laura Bertocci

Design Assistant: Brijae Morris

Ad sales: Midroll

TRANSCRIPT: QUEEN OF REVOLUTIONARY FEELINGS

[Ads]

(0:40)

Aminatou: Welcome to Call Your Girlfriend.

Ann: A podcast for long-distance besties everywhere.

Aminatou: She's Ann Friedman.

Ann: She is Aminatou Sow.

Aminatou: Whew, she is feeling tired today. [Laughs]

Ann: She is falling apart is what I was going to say.

Aminatou: Her life is in shambles.

Ann: She is day one menstrual and her sewer is not working so she can't flush the toilet. That's how she's doing today. [Laughs]

Aminatou: Aww! I'm so sorry baby. That's awful.

Ann: It's fine. Body issues really close to the surface today in every sense, that's what's happening. How are you?

Aminatou: [Laughs] Today is the kind of day that I realize that I use the word tired causally all the time because today I actually feel very tired and no other word fits, you know?

Ann: Tired is one of those words like love where it is totally contextual, the meaning. I hear you. Like there is tired tired, bone tired. There is annoyed tired. There's kind of bored tired. There's a million different experiences.

Aminatou: I feel really grateful that there are always people that you can look up to when you feel like your tank is empty, you know?

Ann: Ugh, tank refillers. My favorite people. [Laughs]

Aminatou: Yes. And so today on the podcast I talk to Glennon Doyle about her new book Untamed and yeah, like a real tank filler.

[Theme Song]

(2:30)

Ann: I have to tell you I became acquainted with Glennon's work when I went to like a live Oprah Super Soul sessions ostensibly for work research purposes. And when she came onstage I will confess to you that I really kind of judged her based on her presentation oh god, what is this chipper, Christian, mainstream woman going to tell me about the world that is going to feel revelatory? And I do feel like by the end of her whatever it is, ten minutes onstage, I was a full convert. I was like I actually do want to hear what this woman has to say about the world and her place in it.

Aminatou: Ah. I love a conversion story so thank you for that. [Laughs]

Ann: Love a story about my judgmental nature being shutdown by reality. I love that narrative. [Laughs]

Aminatou: Listen, I love that narrative because it's so easy to have really strong feelings about people that you think are different from you or people who've tapped into an energy that you don't kind of understand, you know?

Ann: Yes.

Aminatou: And it's just really easy to be like oh, this is phony or it's not real.

Ann: Or it's not for me right? Yeah.

Aminatou: Yeah, or that it's just not for you. And I think that a thing -- like a pattern I'm really trying to break out of actually is I'm like you know, anyone who is on the side of liberation whether it's emotional or spiritual or physical, that's the side I'm trying to be on. So actually I'm going to shut up and I'm going to really listen. You know also sometimes how a book really comes into your life at the exact time it's supposed to come into your life?

(4:05)

Ann: Yes I love that feeling. There should be a long and beautiful German word for it.

Aminatou: Yes there has to be a German word for it because the week that I read Untamed was one of those weeks. It was like life was kind of madness. There was not enough time and I was just feeling a lot of despair about some things in the world and then some things in my life. And it just really grounded me. It really grounded me and I think a thing about Glennon's voice and about her body of work is really this, is she just forces you as a reader or as a listener if you happen to be in the same room as her to really reckon with yourself and to ask a lot of questions about the kind of life that you want to have.

I think that it's a conversation a lot of people are trying to have but she does it in this really powerful way and I have to say all of time stopped for me because I really needed to hear that and I really needed to ask myself all those questions in that moment.

Ann: Ugh I love that. And I also am really excited too about the way that that experience of connection with a writer or a book can sometimes feel unexpected. I mean the way you were like oh right, this came into my world at the right time, that feeling is always a surprise for me, you know what I mean? Like oh, I found a thing I needed here. It's always so pleasant.

Aminatou: Untamed is a memoir and if you've read Glennon's previous books I think that you should really run to read this one also because they just all build on each other and also like wow, never a boring day in the life of this very generous human.

Ann: And if you haven't read Glennon's previous books you might be familiar with her because around the time her last one was coming out there was a lot of really tabloidy -- maybe not a lot, there were definitely a few tabloidy articles about her personal life because the last book was about her marriage which she'd been married to a man for several years. They had three kids together. And around the time she was about to go on the road promoting this last book which is about essentially her choice to stay in that marriage she met famous soccer star Abby Wambach at a book event, essentially fell in love at first sight, and decided to leave her marriage and make a very different set of choices than she'd been making up to that point. And I think it's important to know that context and also maybe not so important because in a way Glennon is a master of telling a story that is personal and highly specific to her but at the same time really finding themes that feel broader and deeper.

(6:50)

Aminatou: The book is really about listening to that voice inside of you, like she calls it the longing inside of each woman, and all of the things that you're kind of programmed to do. It's like society says you're supposed to be a good partner. You're supposed to be a good daughter. You're supposed to be a good mother, employee, friend. All of the things, right? The good girl programming.

And really asking yourself what are the things that you are not content about in your life and how you can free yourself from all of that. I just appreciate it so much and I honestly am finding myself getting a little emotional because I think I have always come at understanding how I feel about this question from a really feminist praxis kind of book, you know? Explain to me the structure and explain to me all the machinations that are at play here. And there's something so beautiful and so human in getting all of that same information but in a way that really just comes from the heart, you know? You're not like in a Feminism 101 class. You're not having an intellectual argument with anyone. It's just like no, truly how do all of these structures conspire in a really personal way to affect me?

(7:55)

Ann: Right. How are they felt within your particular body and your particular life?

Aminatou: Right. And there's just something about that that hit me in a gut level in a way I was just really unprepared to deal with. It was just like really beautiful. So Glennon is a great writer and has a wonderful voice but also is a deeply honest person, like has a kind of transparency I feel that makes you want to be transparent in your own life and let's keep doing that, more of that.

Ann: Ugh, let's do more of that. I can't wait to listen to your conversation with Glennon.

[Interview Starts]

Glennon: I'm Glennon Doyle, author of Untamed.

Aminatou: Untamed! Hi Glennon.

Glennon: Hi!

Aminatou: Thank you so much for making the time today.

Glennon: I mean it's so weird to be honest with you. I listen to you.

Aminatou: What?

Glennon: Usually while I'm puttering which is my favorite activity is puttering around my house. So yeah! I've listened to you and Ann for a long time so this is exciting and a little bit sweaty.

Aminatou: Don't be sweaty at all. You wrote another book!

Glennon: I did.

Aminatou: How does that feel?

Glennon: This one for me is . . . it's like everything that's been on the tip of my tongue since I was ten years old.

Aminatou: Wow.

Glennon: It's just what I needed to say about the world, about myself, about women, about men, about all of it, about faith, about sex. It's a beautiful thing to feel like oh, there's nothing -- I don't have two selves anymore. Like I don't have a secret self and a public self. They've merged completely in this book and there's just nothing to be afraid of or nothing left to hide. That feels really good.

Aminatou: There's nothing left to hide. I'm getting the chills. I'm someone who I lived so much of my life in it's honor or shame, you know? Those are the binaries that I am trying to break out of and I think some of that was I grew up Muslim then I went to this weird Evangelical church and had a church phase. I think that so much of what that reinforced for me is you're either doing honorable things or you should be ashamed of who you are. And just to hear you say how freeing it is to see -- you know, to just be able to stand by yourself and say "Actually this is me, this is enough, and this is all I can do," that seems like a really powerful revelation.

(10:20)

Glennon: Yeah. And so it's interesting because so much of that shame stuff for me goes back to religion also which is why that's a running theme throughout the book. I mean to be a woman who in the public eye left her husband for a woman as a mother, as -- you know, I did the thing that you're not allowed to do as a woman which is just want more. [Laughs] Right? That's like the story.

Aminatou: Right, it's like choosing yourself then wanting more.

Glennon: Mm-hmm. And I think that is one of the things . . . you know, when I fell in love with Abby it was just this very interesting experience for me because I had never been in love before which I know now and I fell madly in love with her and it made me feel really whole and comfortable in my own skin for the first time. The best way I can describe it is you're wearing shoes that are way too tight your whole life then you finally put on slippers or something like that, right?

Aminatou: Exhale -- yeah.

Glennon: Yeah, it's like ugh . . . or you take your bra off after a long day or whatever it was. It's like oh, this is what it's supposed to feel like. And that was such a revelation to me because I had to go outside of what I'd always been told or expected to choose in terms of love, in terms of sexuality, in terms of all of that. I had to go outside of what I was told was honorable to find what fit me which made me wonder if I also needed to go outside of what I had been trained to believe is honorable religion. What I'd been trained to believe is honorable womanhood. What I'd been trained to believe is honorable motherhood.

Aminatou: Yeah.

(12:10)

Glennon: Because one of the reasons why I was so afraid to choose myself was because I was trained to believe -- tamed to believe -- that when you have a baby what you then do is slowly die, right? You just give up all of your desire. You give up all of your emotion. You give up your dreams. You give up your imagination because that is what's best for the kid. That's what we're sold. Then one day when I'm trying to figure out this stuff with Abby, I look at my daughter, my eleven-year-old daughter. She's eleven now. She was nine now. She's looking at herself in the mirror, I'm putting her hair up, and she says "Mommy can you do my hair like yours?"

And I looked at her and I thought oh my god, every time this child looks at me she's asking a question. She is saying how does a woman do her hair? How does a woman live? How does a woman love and be loved? And I realized oh, I am staying in this marriage for her but would I want this marriage for her?

Aminatou: Modeling just this idea that you're not a person, you're really just a vessel for whatever your family needs.

Glennon: That's right.

Aminatou: And you can be a martyr and you can do it really well. It's like people do it all the time. You can outwardly look like you're doing really well but it is incredibly painful inside and all it's doing is chipping away at that person that's inside and it's going to come out one way or the other.

Glennon: It's going to come out one way or the other which I know from addiction it sure does come out one way or the other. To me it's not just that it's painful inside, it's also a horrible legacy. It's so backwards. We think that it's honorable to our children to be martyr parents but it's not honorable to our children because then we're passing it on to our kids. Then the next generation feels guilty for having any sort of self because their mother taught them that real love is not having a self right?

Aminatou: It's dying to yourself.

(14:02)

Glennon: Right? Which is the more religious stuff. So it's like breaking that idea of who is that idea that's been implanted in me that mothers are supposed to be martyrs, who does that serve? Like all of the ideals and expectations that are placed on women, a good woman in every area of her life just slowly disappears and is quiet and takes up no space. Those always serve not us, not our kids, right? They're to maintain power structures.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Glennon: You know, figuring out what fit me, what made me feel finally at peace and in power in my own skin and like I wasn't performing, finding that so outside of the norm, the cultural norm for me made me want to just rip out all the other expectations.

Aminatou: Right. It's like what else don't I know?

Glennon: What else am I just performing that has nothing to do with my real self, right? And there was a lot of that. There was a lot of that in my life.

Aminatou: Right. And you write and you've spoken so much about how every decision was kind of made from this place of you have to be a good girl and then breaking out of that meant you found someone you loved unconditionally and you learned so much from that. And I think when a lot of these stories focus on the romance so much is lost on the what it means for your own personal self-knowledge and what it means -- you know, what it means that you are capable of as a person. It's like if you let yourself be loved then what can't you do?

Glennon: Yeah.

Aminatou: And that message for you is really transcending and changing the communities you're part of because you're no longer performing that other good girl. You're finally yourself.

(15:45)

Glennon: Yeah, in lots of different ways: in faith and activism and even in gender stuff. And certainly in sexuality. Yeah. I mean because what it came down to when I decided to leave my marriage I had no -- Abby and I had never spent a minute alone together at the time I told Craig I was leaving. We had never been alone in a room together. We'd spent the -- we had met one night at a book event. [Laughs]

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Glennon: Launching my epic marriage redemption story so that was inconvenient as all hell but we had never, from that evening which we spent with a bunch of other writers on a dais in front of hundreds of librarians, we had never spent a minute alone together. So for me I knew that there was a very small chance that this thing with Abby, I mean who did turn out to be my wife but . . .

Aminatou: We're here now. [Laughs]

Glennon: Right, we're here now.

Aminatou: Spoiler alert.

Glennon: Spoiler alert. But at the time chances were slim and I knew that but I couldn't un-know what I now knew.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Glennon: Which was that thing, I didn't have that with my ex-husband.

Aminatou: What do you think is the thing -- because I think when you assess yourself, and I think it's a thing we all do, you minimize a lot of the courage that turns out has been inside of you the whole time. It's everything just seems scary. I can't do this. I can't do that. How do you get there? I wonder, and you spend so much time self-reflecting, what do you think it is about yourself that gave you the drive and the courage to do that?

Glennon: Okay well first of all I don't know. I feel like I can give you my best answer right now, and it's so funny to do -- okay, I wrote Carry On, Warrior and then I tried to talk about myself then then I wrote Love Warrior and tried to talk about myself then. You just have a different perspective on yourself each five years I guess. I feel like I'm . . . you know when you go get your eyes examined and they put on new lenses?

Aminatou: Yes all the time. [Laughs]

Glennon: And they're like does this look clearer? Does this look clearer? Does this looks clearer?

Aminatou: And it all looks the same, yes.

Glennon: And it all looks the same. But you're just like B I guess? B? So I can give you my new lens of 43. I think that I knew when I got sober that the only way to stay sober for me was to minimize that two-life thing right? To find myself, like that voice in the stillness. You know that? Everybody has it. You know when you get really still and you just have that knowing? Like you know. It's a nudge. It's whatever it is, like some people call it God, some people call it institution. It's just that knowing you have inside yourself.

(18:25)

I have, since I got sober and started practicing being in touch with that knowing, have learned to believe it above any over thing. Even when every person in my life, everyone is saying you can't do that which is what was happening when I told all the people that I was just real quick going to get divorced six weeks before my epic marriage redemption story came out.

Aminatou: [Laughs] Love it.

Glennon: And was just accidentally in love with a female Olympian, right? It has not steered me wrong. Even when it seems like the dangerous thing or the uncomfortable thing if I stick to that knowing, that inner knowing, even if there's like a bunch of chaos that happens in the middle part, it all ends exactly where it should.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Glennon: And that just keeps happening over and over again and I have had enough practice over my 15 years of sobriety before that happened to trust that knowing regardless of what the outside voices were saying to me, that when I got to that one -- which was a pretty doozy of one, you know? Like there she is, that person -- I had just trusted enough. And my sister who's my person had watched me trust that enough that she was even -- she was like all right, let's do this, behind me one everything. And when I have my sister beside me, you know, I always say if my sister is for me who can be against me? She kind of blocks for me.

(19:50)

So we kind of did it together and as always that thing about there's no such thing as one-way liberation, I knew that if I stuck to what was -- that if I rejected the idea which is another lie that women are told that I can't do . . . I can't follow my heart. I can't have what I need because that will be mutually exclusive to what my people need, right? If I choose myself that is inherently going to be bad for everybody else. That's also horse shit. That's not the way it works. What is true and beautiful for me is also going to inevitably be true and beautiful for my people and that's what's happened. There's a lot of chaos and a lot of whatever and a lot of dust up and now everybody's fine.

Aminatou: Everybody's fine. This is truly . . .

Glennon: Everybody's fine.

Aminatou: I started reading the book when I was on vacation with my family. It's the first time in over a decade our entire family has been together for various chaotic family reasons and the whole time I was like well, you know, my Zoloft is working really well because that's how I can be on this vacation.

Glennon: Amen.

Aminatou: It's like even a day ago I couldn't imagine it. So to read all the stuff you write about this blended family coming together, that really spoke to me in so many ways because for such a long time I always had this idea that everybody else's family was perfect except for my family. My family is the nutty family.

Glennon: Yours is the one. Yours is the one.

Aminatou: To my sister who's listening we're doing great babe. We're hanging in there. But there's always just this idea and so much shame tied to the fact that I thought everyone else had this perfect family and there was something so healing for me reading about your own kind of chaos and how your family comes together that was like oh, it's okay to have some of that chaos because we -- sometimes it's nobody's fault and there was something about the way you wrote about how everyone in your family was reacting to all of these big changes that made me feel like I could be on a vacation with my family.

Glennon: [Laughs] Aww.

Aminatou: I was like great. I was like everyone is going through it and also maybe instead of focusing on what is the image of the family that we're not focusing more on this place of saying like how can we be the best people that we can be to each other, you know? And how can we support each other's dreams? Because I think that you're so right in identifying this thing of if you choose yourself and you choose what is beautiful and good for you you have a fear that it will not translate for everyone else. My idea of being a good sibling is I have to deny myself everything and then it's like everything else works. Like, you know, it's like that emoji with the brain exploding.

Glennon: [Laughs]

(22:30)

Aminatou: I was like what? Other people have families that are not perfect? This is nuts to me.

Glennon: I mean don't you think that's the same idea though of letting go of this idea that you've been sold about what makes a perfect family? Like what makes a good family? What makes a good woman? What makes a good Christian? What makes a good Muslim? What makes a good -- it's like this magical thing when it's the idea that everything's wrong and it's just the picture in our head of the way things are supposed to be.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Glennon: And when you let go -- and that picture has always been planted by somebody who's selling you something. Always.

Aminatou: Exactly. Always.

Glennon: Why am I depressed? Oh yeah, capitalism. It's always the answer right?

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Glennon: So it's that moment of surrender of like oh yeah, if there's no way that a family is supposed to be then I guess I might as well just hang out with these people I've been given.

Aminatou: You know, that's the message for me. I'm just like oh, I'm just here. I'm not perfect but I'm here and so the mess you have here is what we're going to all work with.

Glennon: It's what we've got.

Aminatou: I'm like this is what we've got. But I think if everybody operates on that level sometimes magic happens.

Glennon: Yeah.

Aminatou: It's a place of you really have to trust that everyone is sharing where they're coming from right? And so it's why I think so much of your work connects with so many people because you say the thing that so many people don't realize they're allowed to say in the first place, you know? It's like you give permission to say okay, everything's not perfect or here is my fear. Here is my hope. Here is my goal. And I think that even as someone who works in this medium where we tell stories all the time I am constantly surprised how much so many people don't tell their story. That's the kind of holding back that is . . . you know, I'm like you can't break out of that unless you're afraid to say what you think and what you want.

(24:24)

Glennon: And that's because they think that there's a way that they're supposed to be and they're not that way. And so that's the shame, right? Whoever they are, whatever their past has been, whatever their feelings are, whatever their relationship is, it doesn't match this cultural idea of whatever that thing is supposed to be. And that's the split, right? That's where we get shame.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Glennon: And I think I've just learned . . . I learned, and I feel like everyone should go through recovery right? Recovery from addiction is like where you learn that the only way to survive is to say the thing. To say the thing that you think you can't say.

Aminatou: Right, because you have to say it.

Glennon: Right. That's the only thing that will . . . it's not the pain of life that takes you out of the game, it's the shame about the pain of life. Then you keep it inside and it just infects everything.

Aminatou: You were saying earlier before we started recording that part of why you think you are always early to things is because you think that it's a kind of -- like it's a learning from being in recovery.

Glennon: Yeah, being drunk. Being drunk all the time.

Aminatou: I'm curious if you would talk a little bit more about that.

Glennon: So I became bulimic when I was ten and then that morphed into alcoholism and then I stayed drunk for much of my life. Not like -- it was a problem, sick, sad drunk until I was 25 and I found out I was pregnant and I got sober. And when you spend your kind of formative years or your early adulthood as an alcoholic you end up hurting a lot of people. You end up being the person no one can depend on. You are kind of like a joke in your friend group. You're a disappointment in your family. You're the one who doesn't show up for the baby shower. You're the one who makes an ass out of yourself at the wedding, whatever.

(26:15)

So you kind of develop this self concept that's like I'm irresponsible. So I got sober when I was 25 and I guess what I was joke about was I -- my sister would tell you I have a late phobia. It's not normal. If I am more than five minutes late my heart will start going, my hands will start sweating, and I think it's because I'm always just trying to prove that I'm responsible now, you know? I'm trying to . . . it's not really a making up for all of that; it's that in my heart of hearts I never know if I was a responsible person my whole life and I was just, you know, that was being covered by the alcohol or if I'm actually an irresponsible person and just acting now. [Laughs] I'm not sure. So I do think that I guess . . . I don't know if it's leftover shame but it's a leftover -- it doesn't feel like shame, it just feels like a little bit of identity confusion.

Aminatou: Let's take a quick break.

[Ads]

(29:40)

Aminatou: I want to ask about the process of writing this. You write -- there's so many parts of your life and some of it is so personal. How do you . . . this is truly a selfish question as someone who just wrote a memoir, how do you square all of that with the fact there are people very close to your life who the book is also about? Like do you just write it all then you're like here's the book, read it and tell me what you think? Or are you in conversation with your family and with Abby? Are you negotiating all the things that you're writing about as you're writing about them?

Glennon: Well I guess a little bit of both. First of all I know that there are writers who I think Anne Lamott says well if they wanted me to write better about them they should've behaved better.

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Glennon: There's that strategy which I think is admirable. I admire that strategy.

Aminatou: I love it for someone else. [Laughs]

Glennon: Me too. Me too. But I can't and don't do it that way. I don't think there's ever been a person in my real life that I've used as a character in my memoir or my -- that doesn't come across as their best self, like as the most loving, true . . . if there's a butt of any joke in an essay it's going to be me. If there's two people in a story, if it's me and Craig, you're going to learn about the strength of humanity from Craig and the bullshit from my behavior is how I try to write it which luckily isn't hard. [Laughter] It's actually pretty consistent especially married to Abby with how it goes.

But with Craig I always sent him everything I'm writing. With this book it's so . . . I don't know why he's so freaking supportive of my writing but he is and he read the whole book and he just asked me to change one sentence that was about Tish. It was just something he felt like wasn't . . . that maybe a few years from now she wouldn't love and he thought all of his parts were beautiful which I thought was amazing.

(31:40)

And Abby is . . . Abby, her favorite thing on earth is when I write about her or talk about her. After every podcast afterwards I'll call her and she'll go "Did you talk about me? What did you say?" She loves when I talk about her. But she is so uncomfortable with me talking about sex.

Aminatou: Wow interesting.

Glennon: I know, it's very interesting. She's very obsessed with talking about sex privately with me and her which is a new thing for me. I could start sweating now thinking about the amount -- because I've never talked about sex in my life with anyone. But then when I'm talking about it in public it kills her to death. So the essay that I wrote in the book about sex.

Aminatou: Sorry Abby. [Laughter]

Glennon: Yeah, hi babe. Hi babe. Just press mute now. It was a fun exercise because it was like I wanted to write it in a way that she thought was beautiful, that made her proud and not uncomfortable, so that was kind of like a back-and-forth. And when I gave it . . . it really wasn't that much of a back-and-forth. It was a back-and-forth with myself. And then I gave it to her separately, then the whole book, and she loved it. But even when she was reading it she was going oh my god, oh my god, oh my god.

Aminatou: [Laughs] I love it. You find out everyone's, you know, what their thing is.

Glennon: Yes!

Aminatou: Because everyone has their own boundaries which I really respect. People are different, man.

Glennon: I know. But you know what? I don't do that with my parents. I don't ask their permission. I feel like I try to be really generous. Being a parent now I know you just freaking do the best you can with what you have and they did a kick-ass job and also there are some things that could be discussed. [Laughs] But I just feel like I'm being generous and I don't feel like asking for permission. And that's so . . .

Aminatou: Another boundary. Love it.

Glennon: Right, right, right. So I guess it's different for everybody.

Aminatou: You and your sister are very close and you have that relationship that I'm like yeah, you're sisters but also you are friends.

Glennon: Oh yeah.

(33:53)

Aminatou: Which is such a distinction when you have a sibling, you know? You're definitely like there are the siblings that are your friends then there are the siblings that are your siblings.

Glennon: Your siblings. [Laughs]

Aminatou: Which is a thing that people with siblings understand. You're like great. Can you talk a little bit more about how that friendship develops the older that you get? Because I think that that's . . . you start having to lean on your siblings for really adult kind of shit and it does feel very different if your sibling is your friend versus just a member of your family.

Glennon: Yeah and I can't, like for my sister and I, like friend? Whatever we are is like not . . . it's beyond that. It's like I would almost think if I weren't so committed to never changing it ever it's almost like codependent. We're like barnacles on each other.

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Glennon: Right? It's not . . . what we go through feels like if it's happening to her it doesn't feel any different than it's happening to me. Actually I think it's worse. It's worse. If something happens to her it's worse for me than it is for her and if something happens to me it's worse for her. We've been through so much and I was so sick for so long and she was so scared for so long. There was this point because we were inseparable then I kind of fell into addiction and was just gone for so long. And at some point with an addict you get to the point where -- she said this so beautifully recently. She said that there was a point in my addiction that she had to stop trying because she knew if she didn't put up a boundary with me that if I ever did get sober there would be nothing left, which I thought that was so brilliant. Like it's so hard to offer anyone any wisdom during addiction because it's such a breaking mess but that I thought was really important. Like make sure that you don't get past the point of no return when the person . . . so there's something left, you know?

(35:55)

The day I decided to get sober she's the one who literally picked me up off the floor and took me to my first meeting and ever since then, you know, she went through a divorce and then moved into my house and we went through that together. And then she moved to Rwanda. She was a lawyer and she went there to help prosecute child sex offenders in Rwanda and I was so upset she left but it's not like I could be like "Stay with me! Don't go prosecute child sex offenders."

Aminatou: Don't go do your iconic job. Stay here. [Laughter]

Glennon: Trust me, I did say that because that's who I am.

Aminatou: That's a thing siblings do. [Laughs]

Glennon: Right, because that's just who I am. But when I was gone that was the first time I'd been left alone. My life, like she's my person, my . . . and so when she left that was scary as shit and that's also when I started writing because she brought -- I wrote this thing on Facebook that went crazy. She brought me a computer to my home when she came back for Christmas or something and she brought me a laptop and she said you will -- I have to go back, I'm going to go do my job, but you're going to get up every morning and you're going to write. And you're going to write using that voice you used in that Facebook post because this is what you were born to do. I still have the letter she gave me with the computer in my office.

So I did because I just do what my sister tells me to do, you know? So in many ways she's what started this. It's so -- it's all so intertwined, you know? Everything with Together Rising, everything with my career we're doing together. There's nobody on my team who doesn't know my sister runs the show. [Laughter] You know? People probably think oh, that's so sweet that Glennon's sister works for her. It's like the total opposite.

(37:48)

Aminatou: No, it's like we're working together in tandem to free the world.

Glennon: Exactly! We're like two halves and we have different strengths completely. When it comes to friendship I do think it's kind of . . . it was so interesting when I fell in love with Abby because it was like oh my god, there's like a third of us now? It was a little bit jarring at first. I think there was a little of like wait, what do we do with another girl? Husbands are one thing but this is encroaching territory right? So that was a shakeup and thank god now they're -- we're like a braid, the three of us.

So one of the things I love so much about your work is it's just so . . . it's such a loss that we don't talk more about different types of love stories besides this romantic thing. My relationship with my sister since I was born has been the great love of my life, you know? Until now. Abby we know you're the one now.

Aminatou: You can put your headphones back on from the sex moment. [Laughter]

Glennon: Right, right.

Aminatou: She's still not listening. You're so right to identify that and it's why I was asking about your relationship with your sister because I think that, you know, there's so many scripts for how you can be a family but there's also a lot of scripts for how you can be in love and being in love can mean so many different things right? It's like are you in love with someone that you are sexually compatible with? Are you in love with someone that you just love them in this deep, platonic way and who is to say that those two things are not as explosive as the other?

Glennon: Absolutely!

Aminatou: And there's so many scenarios for that and I think there's something . . . so much is lost because the script that we prioritize is this romantic script which I think also honestly does a disservice to people who are in romantic relationships, especially straight people who are in romantic relationships, because you feel so boxed into this is the script and this is what you do and then it's like here's the picket fence. Here's the children. Here's how we talk about each other. And I'm like that's its own kind of jail.

Glennon: It's a cage! It's a cage then we wonder why people need to bust out.

(40:00)

Aminatou: Right. And it also just doesn't honor that . . . you know, people need all sorts of different things and they need them from different people in their lives. And part of why your work connects so many people is it is that thing. It's saying like okay, I'm not weird. I'm not different. There's no norm.

Glennon: There's no norm.

Aminatou: The norm is that you should just say what you have on your heart. That is . . .

Glennon: There is no norm.

Aminatou: Everyone is the -- you are the . . .

Glennon: And you get to figure it out for yourself.

Aminatou: Right.

Glennon: For yourself. You don't have to match yourself to some other idea of what that thing is supposed to be. You get to figure it out. Somebody makes up the norms and we are all somebody, right? We all get to make . . . I mean I've been thinking of it so much recently with even the word mother. The question how is are you a mother or not? What does that mean? I just read [0:40:48] new book which is so freaking beautiful. And her -- one question that got me so much is she said "What will you choose to mother into the world?" Like it's not just an identity that you have that you have babies out of your vagina or adopt. It's like whatever you're nurturing into the world, that is the definition of mothering right?

Aminatou: That's what you're mothering. Yeah.

Glennon: And I think it's so cool because I've always played with that in my mind because some of the people that I actually go to the most for parenting advice and who I think mother me best in the world have no children. Like Liz Gilbert is one of my best friends and I almost exclusively ask her for parenting advice. She's one of the most nurturing, mothering people that I've ever met in my life.

And so even shifting that call like this is what a mother is supposed to look like and turning it into a verb, it's like an energy. It's like a creating, nurturing energy.

Aminatou: It's like all of -- you're right, it's like all the scripts are about putting people in . . . it puts you in your place, right? It's a place where you are a compliant person. You're not rocking the boat. So much of this kind of personal growth is really just yeah, for as cliché as it sounds, you've got to be okay with being uncomfortable because that comfort is actually not comfort. It's compliance.

Glennon: It's killing us! It's killing us.

(42:08)

Aminatou: You know what I mean? It's a kind of compliance that you don't understand but the minute you know a little bit different you can't live that way anymore and it's so hard.

Glennon: And here's the deal, I . . . okay, this is going to sound so cheesy but I actually believe it's the answer to saving our world. I do.

Aminatou: Tell me. Tell me everything.

Glennon: All right. My secret belief is I don't think that we should just all step out of line and out of our cages and out of our social norms because it feels good and because then we'll have amazing lives which is true, okay? It will feel good and we will have amazing lives. But over time there's thing that happens where we're born. We're born with these inherent selves with this potential for this one thing we can release onto the earth, like our beingness, our self, or whatever. But then we are socially programmed. We start to internalize our social programming around 10, okay? That's when we start to lose ourselves in order to fit into these categories that culture has put in front of us. You are a girl. This is how good girls act. You are a Christian. This is how good Christians act. You are a white woman. This is what white women know and pretend they don't know. This is what an American does. And all of these lanes were put in where we have to perform our role and the reason we have to perform our role is so that we can have belonging because each of those is a pack of people and we know inherently that we need a pack to survive. And the second we step out of that we will be shamed by the pack.

I think that evolutionarily it makes sense. We have had to stay quiet and we have had to stay in line so we could have the protection of the pack for our survival. But I think at this moment in time our survival depends on us resisting that urge completely, reversing it even. That the future of our planet, of religion, of our democracy all depends upon people now abandoning the pack enough to regain their own integrity, right?

(44:00)

Because imagine a world where Republican congresspeople stopped just pretending not to know the truth or refusing to know the truth so they could toe the party line. Imagine if a bunch of Catholic churchgoers, people of faith, actually said hell no to the abuse scandal and walked out of the pews. Imagine if men started stepping out of line with patriarchy. Imagine if white women started stepping out of line with white supremacy. Imagine if employees at corporations who are ruining the earth started to step out of line. I think the return to self and return to integrity at the expense of the pack is our only hope.

Aminatou: It's so interesting hearing you talk about this because I think you and Abby have been really vocal in talking to the white woman pack. You know, in a world where we're preaching solidarity and we're saying we're all allies what it means to both understand your privilege maybe and to use it in ways that are helpful to everyone. And I remember Ann interviewed you maybe a couple years ago in New York Magazine and really the thrust of that piece was that. I think that over the years you're someone who has been very vocal about the fact that a huge portion of your audience is white women. Are you seeing something shift? Do you think that it's been useful? Are there things that are making you feel more hopeful? Because every day just seems like more doom and gloom all the time and I really reject the doom and gloominess of it all because it's just like for me personally that is not a way . . . I can't live life if there's not one thing to look forward to every day.

Glennon: You don't even drink coffee so you have nothing else to look forward to.

(45:50)

Aminatou: I don't even drink coffee. I'm not just thinking about the election that's coming up but I think over the last three years and four years I'm just like if as women we can't even find a way to be, you know, not on message but really in a way where I'm like okay, I trust that everyone is doing their little . . . everyone is pulling however amount of wait they're pulling. I just have a really hard time seeing how are we going to change the world if we can't change this one . . . it's not a small thing but I'm like if this thing is not working how can everything else work?

Glennon: I mean I would just -- being completely honest with you nothing comes to mind right away in terms of the rhetoric getting better or the conversation getting more open or easier. At the moment I will tell you that Together Rising and the way that that's working is giving me . . . that's what keeps me going in terms of hope. It's not the freaking Twitter conversations or like . . . Jesus.

Aminatou: What? You're not scintillating, amazing philosophical debates on social media like the rest of us? Wild. [Laughs]

Glennon: That's, you know, no. Although I will tell you that my Instagram community is pretty thoughtful and nuanced and bad-ass. I have some very good conversations on Instagram.

Aminatou: I know. I'm just waiting until someone ruins that for us.

Glennon: No, they can't.

Aminatou: I love Instagram. I know!

Glennon: They can't. I will fight. I will fight for my Instagram community. Sometimes I think okay, those conversations that are happening are not as real to me as what goes on with Together Rising.

Aminatou: Of course.

Glennon: That's real. And one of the cool things that we . . . our job is we fund raise. We crowd source money for different causes and we have raised about 24 million dollars I think at this point and that is awesome but not the coolest thing. The coolest thing to me is that a long time ago when we started answering the call to these different crises going on in the world whether it was the Syrian refugee crisis or the families being separated at the border we started talking to people on the ground. One of our priorities was like no secondhand sources. We are going to go. We're going to talk to the people being affected by these things and figure out who's on the ground already doing the work.

(48:00)

What we hear is people are in their homes. They learn about something in the world. People are good. Their hearts break. They want to give. They want to do their little part, right? But the people that they often end up giving to are the big organizations because they know about the big organizations because those are the people with the big marketing dollars.

What we found over and over again is in today's world where crises are happening fast and we need the help on the ground fast it's not working to give funds to those organizations anymore because every time you talk to them, "All right, we've got $78,000. Here's what we see on the ground. Here's what's needed." And it will literally be like "Okay, we hear you and we'll get back to you in six weeks." It's like what? We need it by 7 p.m.

Aminatou: Yeah.

Glennon: So over and over again after this happens for a while you're like okay, we need to find the . . . we have found in any scenario that the most effective, scrappiest, most respected groups, boots on the ground groups, are almost always led by women and they are disproportionately led by women of color. They don't get the funds.

So what's hopeful to me is we have a situation going on with Together Rising where we're like a bridge, right, between all these brokenhearted people in their houses who by the way are mostly white women right? That's my demographic. They're giving funds and those funds are going directly to largely women of color -- not always -- on the ground doing the hard work they've been doing forever. And that feels hopeful to me that there's this connection happening.

So I think about Together Rising when I think about hope and I also think about my actual life that I can touch in my . . . because I live in Naples, Florida so it's the Trumpiest Trump that ever Trumped land. It's like okay, there's one other gay person in Naples and she lives with me.

Aminatou: [Laughs] So glad y'all found each other.

(50:00)

Glennon: Right, right. So it's fascinating to live there because it puts me in a situation where I'm always, always forever having to practice what I preach which is that I'm always having to fucking say something. And honestly it usually doesn't go well. I'm not saying it always ends in this amazing, you know, illuminating experience where we see each other's side. It sometimes it gets really uncomfortable and then it's awkward to see each other for a while. But I actually have had a few good conversations with people after moments like that and it makes me more committed to the idea of stepping out of line a little bit and saying the weird, uncomfortable thing.

Like often for me it'll be like -- we'll be talking about the schools our kids go to or something and I'll tell them where my kids go to school and they'll be like "Really? Your kids go there?"

Aminatou: [Laughs] With those people.

Glennon: And they don't add that but that's what it means!

Aminatou: That's always what it means.

Glennon: But you're supposed to get away with the really. And what Brittany Packnett taught me, which this strategy is so good because for a while I was just doing speeches. What Brittany taught me is when you hear that you just ask questions because racism, homophobia, misogyny, it doesn't stand up to questioning.

So my favorite thing to do is just when I get the "Really?" is to stay there and keep asking questions like "Oh wait, you look confused. What do you mean?" And then it's like "Oh, well I just mean, you know, because it's just a different . . . like there's different . . ." And it's like different what?

Aminatou: You make them say it.

(51:50)

Glennon: Eventually you get to that thing that's hidden that's not allowed to be hidden anymore. It's just not allowed to be hidden. Like if you're going to say it you just have to fucking say it. I think those are the things I care about much more than like the Twitter shit is so much posturing and performing that I really can't . . . I very much -- I have had those conversations in real life over and over again and I know how freaking uncomfortable and hard they are and I don't believe that 90 percent of the people on Twitter are having those conversations in real life. I think it is very much easier to be brave on Twitter than to be brave at the bus stop.

Aminatou: Oh are you kidding me? 100 percent. Well you're about to go on this very big book tour. A lot of people will be talking about your books. Who do you want this book to speak to and what do you want people to walk away knowing?

Glennon: Hmm. So the person that I most want the book to speak to is the person that I thought about the entire time I wrote it, the person I dedicated it to, the person who's woven throughout the entire book which is my daughter Tish. This is so weird but I often think like okay, so if I only have one more book left, like if I die soon, which is the book I'd want to leave for my kids? So weird. Tish is -- I have changed the way that I think about myself through raising Tish because Tish is a really, really sensitive kid and I was a really, really sensitive kid but I thought there was something wrong with me because I was so sensitive so that's why I started numbing myself out with food and then lost myself for a really long time.

So I actually have had this narrative in my head my whole life that's like I'm broken. I'm crazy. I mean I've been in therapy my whole life. I've been medicated my whole life. I've been to a mental hospital. [Laughter] Like there's been some corroborating evidence to my narrative. So anyway raising Tish and watching her she -- her heart breaks for things in a way that is, well, it's highly inconvenient. [Laughs] It's annoying as shit sometimes honestly.

(54:00)

And so I can see how a child like me would make a family want to tell her she's too much. But what I know now to be true is that the sensitivity that I had when I was little that I thought meant there was something wrong with me is the same sensitivity now that makes me a good writer. So what I know now is there was never anything wrong with me. The stuff that I was born with that made my life a little bit hard in the beginning is exactly the stuff that I was born with because I need to use it to get my work done on the earth. Consider the revolutionary idea that there was never anything wrong with us except for the idea that there was something wrong with us.

Aminatou: I will take that. Glennon thank you for giving us your time today. Thank you for being extra. Thank you for giving us permission not be extra and yeah, just really thank you for always creating space for people to say like where they're at and who they are and who they hope to be. Like that means a lot so thank you.

Glennon: Same to you! Same to you and next time I hear you I'll be in my home on my phone listening to you on Call Your Girlfriend. Thanks for the work that you do.

[Interview Ends]

Aminatou: Glennon Doyle.

Ann: Ugh, Glennon Doyle forever. Really, truly, deeply.

Aminatou: Queen of being a revolutionary. I love it.

Ann: Queen of feelings. Queen of revolutionary feelings. Like yeah, really on an emotional level. I feel like this book is something that is going to change a lot of people's experience of the world. I really do.

Aminatou: Yeah, you know, and it really . . . when people take the time to share the truth about their life it really changes people. It changes people and it's one of the most generous things that someone can do for another human so like more kindness and more transparency, that's what I want this week in my life.

Ann: More truth, no big deal. [Laughter]

Aminatou: NBD.

Ann: All right, I'll see you on the Internet.

Aminatou: Okay boo-boo. I'll see you on the Internet. Take care of yourself. You can find us many places on the Internet: callyourgirlfriend.com, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, we're on all your favorite platforms. Subscribe, rate, review, you know the drill. You can call us back. You can leave a voicemail at 714-681-2943. That's 714-681-CYGF. You can email us at callyrgf@gmail.com. Our theme song is by Robyn, original music composed by Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs. Our logos are by Kenesha Sneed. We're on Instagram and Twitter at @callyrgf. Our associate producer is Jordan Baley and this podcast is produced by Gina Delvac.