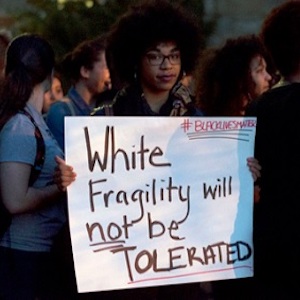

White Fragility

8/31/18 - Let's talk about race, baby, and what white people really mean when they say they don't see it. Whether it's willful ignorance about collective racial identity or an unexpectedly defensive flare-up from someone who claims to be progressive or an intersectional feminist, white fragility has serious consequences. We discuss its impact on people of color with Rachel Cargle, and explore ways for white people to break down internal barriers to growth with Robin DiAngelo. If you are white and listening to this, stick with it, even if you're confused or uncomfortable.

Transcript below.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Overcast | Pocket Casts | Spotify.

CREDITS

Producer: Gina Delvac

Hosts: Aminatou Sow & Ann Friedman

Theme song: Call Your Girlfriend by Robyn

Composer: Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs.

Associate Producer: Destry Maria Sibley

Visual Creative Director: Kenesha Sneed

Merch Director: Caroline Knowles

Editorial Assistant: Laura Bertocci

Ad sales: Midroll

TRANSCRIPT: White Fragility

[Ads]

(1:40)

Aminatou: Welcome to Call Your Girlfriend.

Ann: A podcast for long-distance besties everywhere.

Aminatou: I'm Aminatou Sow.

Ann: And I'm Ann Friedman.

Aminatou: What's up baby?

Ann: Oh, you know.

Aminatou: Listen, the correct answer to "What's up?" is "Nothing but the rent, baby." [Laughter] I love it when old black folks say that. It always makes me very happy.

Ann: It is an always-true response.

Aminatou: Always.

Ann: Like that's the thing about it, yeah.

Aminatou: I was like it was true forever ago and it's true today so it's great.

Ann: Ugh. Are you ready for the interviews in today's episode?

Aminatou: Listen, you did all the work so I am very ready. Alert and ready. Tell me everything.

Ann: Well today's episode is all about white fragility.

Aminatou: [Sighs]

Ann: And what happens when white people are presented with uncomfortable realities for them about race and the way it operates in our society and the way they operate in a racialized way in society. Especially white people who consider themselves progressives and feminists -- and/or feminists. That is what today's episode is about.

Aminatou: You know, nothing but the rent baby. [Laughter]

[Theme Song]

(3:15)

Ann: Robin DiAngelo who is an academic, a tenured professor of multi-cultural education -- who knew that was a position?

Aminatou: Love it.

Ann: At Westfield State University. She comes from a background of doing a lot of diversity and inclusion trainings in corporate environments and she noticed this thing that would happen when she talked about race with a group of let's say 99 out of 100 employees or 96 out of 100 employees being white. The reactions they had when she tried to talk about the realities of the ways that race has shaped our society and about racism as a force and about whiteness as a thing, they would just freak out. Like this defensive behavior that I know everyone who is listening to this podcast who is a person of color is like "Yes, duh, obviously."

Aminatou: Oof.

Ann: I don't know if that's your reaction to that.

(4:05)

Aminatou: You know, some of my best friends are white. [Laughs] My doctor is a white person. My banker is a white person. I don't know what you're talking about. That's so interesting, like you're right about that. And it's something that it took me a really long time to understand what was going on with that and I realize that it's because oh, people who are not white actually talk about race all the time. It's like we're racialized people. And so I never realized that was not true for people who are not of beautiful colors so it just had never occurred to me.

Ann: Right. The melanin-deficient are often not culturally and socially pushed to think that this is an idea that they have to have any kind of feeling about whatsoever. Like this is part of what her work is about. But anyway, so these reactions, these defensive and angry reactions that she was noticing over and over, she spent a lot of time thinking about where does this come from and eventually wrote an academic paper that later became a book terming it white fragility. It also seemed totally misrepresentative to have this conversation about white fragility without having an equally-important conversation about the ways in which white fragility is experienced by people of color and in particular women of color. Are you familiar with Rachel Cargle?

Aminatou: Yeah, this is . . . her story and the parallel to talking to Robin DiAngelo's really fascinating.

Ann: Yeah, so Rachel, I became acquainted with her work on Instagram as I think a lot of people have. She is @rachel.cargle, C-A-R-G-L-E, and she's an activist and a writer currently attending Columbia University. And recently after the murder of Nia Wilson which do a Google if you do not know the name Nia Wilson, she noticed that she was not seeing a lot of conversation about this woman and about the injustice of her death on accounts associated with prominent feminist voices who happened to be white. And so she ran a campaign that was like "Hey, maybe what you can do is ask your white feminist fav to talk about this woman and to talk about this issue and let's see if we can't bring some more attention to it." And as a result a few people got very, very angry and . . .

(6:25)

Aminatou: Which people got Angry, Ann?

Ann: Good question.

Aminatou: Who got angry?

Ann: You know, they were white women. They were white, feminist-identified woman.

Aminatou: You know, fragile and yet angry. What a conundrum.

Ann: Listen, and so she had a lot to say about not only this experience -- I hope I did not give away the punchline though but it sounds like you might've been able to guess the punchline anyway.

Aminatou: [Laughs]

Ann: So Robin DiAngelo is kind of . . . she's this academic who's looking at a big phenomenon in writing in pretty broad terms, although she does talk about her personal experience in the book, and Rachel is a person who is experiencing white fragility in a violent and direct way and is experiencing it in real-time online. And I think talking to her as someone whose work is rooted in social media is particularly interesting on this question because it is such a real-time and public-facing way to do this work.

[Interview Starts]

Ann: Rachel, thank you so much for being on the podcast today.

Rachel: Thank you so much.

Ann: For people who are unfamiliar about your work maybe you can talk a little bit about who you are and what you do by way of introduction.

Rachel: Yes, my name is Rachel Cargle. I'm currently living in New York City. I'm attending Columbia University. A lot of the work that I do is public on social media. I don't know, whatever millennial social media life is. But a lot of my work is public and an intersection of race and feminism. So I basically just facilitate a lot of intellectual discourse and really meaningful conversation around what it's like to be a black woman and what it's like to be a black woman feminist and just how feminism works and looks through the lens of race.

(8:14)

Ann: Yeah, I want to talk about maybe a specific example of that experience that you're talking about with being a facilitator and a leader and someone who's really advancing that conversation and your perspective on Instagram in particular. So maybe you can talk a little bit about what happened after Nia Wilson was murdered and you put out a call for more attention and frankly outrage as a result of that.

Rachel: Yeah. So after the murder of Nia Wilson I realized that a lot of my feminist friends and people who call themselves leaders of the feminist movement under various platforms weren't really talking about it even though it was a tragic death of a woman in such a vicious way. And so I kind of just re-posted something I saw that put a call out asking where's your favorite white feminist and how come she's not talking about Nia Wilson? And a lot of my followers began to tag a lot of the women who they were like "Yeah, why haven't I heard from you? Where are you at on this conversation?"

And it was incredibly interesting because there were people who were seeing it and they were just as surprised and outraged not just at her murder but also at the way media wasn't covering what had happened even though it was so specifically race-based and so specifically tragic that such a young woman would've been -- literally she was just stabbed on a metro platform. And so a lot of those who were tagged stood up and said "Yes, I hadn't heard of this. I'm outraged that media isn't covering it but I'm also outraged and demanding justice alongside you." But there were also a lot, in a few places in particular, where there was tons of defensiveness and tons of just being offended that they had been called out in such a way where we were questioning what their stance was on feminism and whether they were really here for all women or they were there for women who experienced life like them regardless of how much they claimed inclusivity, they claimed intersectionality. We were calling them to show that in that moment and there's a lot of very interesting, interesting backlash at the way they were called into this conversation.

(10:33)

Ann: Yeah, and maybe you could talk a little bit about what that looks like because I think that an experience that white women who are talking about politics online have maybe had is like a man saying "Ugh, how dare you say this is something I need to care about," or have a defensive reaction towards them. And I think that often it can be hard to recognize A) what that behavior looks like and the effect that that has. So maybe without naming names but just kind of describing the general tenor of the sort of more backlashy responses, can you talk about what you were hit with in response and what effect that had on you and how you felt?

Rachel: Yeah. I think that what you're referring to, and it's so interesting as a black feminist activist, I've learned unfortunately that a lot of the white women I talk to refuse to really accept what's happening in terms of race and feminism unless it's put in the light of the patriarchy and men and how they've been treated by men. It seems to be so hard for white women to accept that they are both oppressed by the patriarchy just as all women are but they're also oppressors to black women and black communities as a part of a country that was built on white supremacy.

(11:50)

And so there's a lot of frustration and confusion and just this internal grappling that white women are dealing with right now after being called to recognize these things and it really showed up in this instance where they had to realize that they might have been part of the problem and us black women were calling them to task in order to really display the intersectional feminism or the social acceptance they claimed they were a part of.

So a lot of the things that show up in these instances are white women often come and say well, you know, showing themselves in what it is they've done for black people or why they did what they did or why they -- it's like a constant use of the word I and Me and My concerning their feelings above all else. That's part of the conversation.

And one thing that I always use to combat this and really bring it to light is when you hurt someone and you step on someone's foot you don't say -- and they say ouch -- you don't say "Oh, I didn't mean to hurt you so stop whining about it." You don't do that. You say "Oh wow, I'm so sorry I hurt you." You don't explain why you might've hurt them. You don't explain something in your past that led you to this point of hurting them. You literally make sure they're okay, you say sorry, and you move on. And that's something that I read. That was the best example that I can always give around that.

There's also a lot of white saviorism which is also when white people feel like anything they've ever done for a black person should be enough. And so in the instances where we were calling people out there was a very bizarre listing of a resume of everything they've ever done for a black person so that should dismiss them from having to do anything now. Everything from "I'm nice to the black kids in my neighborhood" to "I've donated money to the local black college," things like that where it's like don't you all know how much I've done for you? And it's just very dismissive of the dynamics of the black experience to where if we truly are intersectional we're continuously ensuring that we're all safe and that justice is served for all of us. People ensure that they bring up love in order to dismiss or not have to deal with a lot of the very real, hard, muddy things that are happening. They'd rather dismiss it with telling us "Why don't we just love? Why don't we just have peace? Stop being so divisive." When the truth is we can't ignore things. They're not going to go away just because we ignore them. They're not going to turn into this cloud of love if we just say we love enough when talking about incredibly hard things like racism.

(14:33)

Ann: You recently posted an excerpt -- I believe you said a representative excerpt -- of some of the emails you get. The gist of the email is why not teach instead of chastise? So the kind of argument, calling in rather than calling out.

Rachel: Yeah.

Ann: And I think this hits really close to home for me because on the podcast we've been talking about race and feminism for years and I know Amina isn't online right now but my co-host is a black woman. And the reaction that we -- first of all being able to display different reactions to something when a listener is kind of saying "Uh, don't know about this . . ." We've gotten a lot of mail like this too that's like "Hey, why are you being mean to this person who has maybe got potential to change?" And I think one of the responses that we tend to give is it doesn't always do your friends a service to be like "You're great. You're great. You're great." Like sometimes in order to be in solidarity with someone or be in a movement with someone or be in a friendship with someone you have to say "Guess what? You're not doing great." [Laughs]

Rachel: Yeah, yeah.

Ann: And that is a hard truth that you have to hear and be able to accept as well and accept that it's coming from a place of at least some level of shared values if you're both using this term feminist.

Rachel: Yeah.

Ann: And so I'd love you to talk about that, calling in versus calling out.

(16:00)

Rachel: Yeah, for sure. Whenever I do those things there's always someone who gets offended. And I think that is really important, especially for my work as an activist and a teacher, by showing these examples we're all learning language to have more meaningful conversation when a thing continues to show up. In conversations with each other; in conversations with the public, with strangers. As we continue to dissect problematic conversation it not only calls it out as problematic but it also says "Hey, this is how you continue this conversation. This is how you diffuse it, or this is how you come into it with more meaningful intellectual discourse as opposed to just arguing back-and-forth, throwing opinions, things like that."

One thing I constantly have to remind people is holding each other accountable is not calling out. Holding each other accountable is not shaming. Holding each other accountable is not telling one person that they're a bad person and that they're the worst thing that's ever happened. It's literally saying "Hey, I recognize that you want to be a part of this and in order to be part of it in the most efficient way possible this is what needs to happen." And if we look at it in any other aspect of living I think we all appreciate being held accountable in order to ensure we're really giving our best selves to the greater good.

And so when people get offended by being held accountable I think that it's either showing us that they weren't really wanting to be part of this anyway or they still have a lot of growing to do in order to really be a meaningful, efficient part of what's happening. And so I think that whenever people start getting defensive it shows us so much about whether they're a part of work or not. And I think especially for black women it's so disheartening when we're looking to ensure a more inclusive feminism for us because this has been a very racist movement from the beginning, looking at suffrage and how people like Susan B. Anthony were quick to discriminate against black women, quick to tell black women that they needed to march at the back of the line, quick to throw black women under the bus when they were going out to campaign for their own right to vote as white women. And I think as we black women are continuing to say, hey, this is what we need in order to ensure that we're being heard. If you really are about having an inclusive feminism, and when there's offensiveness to that, there's a lack of trust that happens. And that's where it gets scary because it's heartbreaking to think that such a needed movement can be an unsafe place for us.

(18:44)

Ann: Ugh, I don't know. I've been thinking about also in preparing to talk with you about the way that a lot of your work centers on social media and is therefore about this very public manifestation of these issues, right?

Rachel: Yeah.

Ann: Because when I think about it I'm like okay, there are things that I post about on the Internet. There are things I write about. There are things I talk about on the podcast. And then there are things I'm doing, right?

Rachel: Yeah, yeah.

Ann: Which obviously writing and talking is a doing as well. But I guess what I'm trying to say is there's a lot of different layers to everyone's practice of feminism.

Rachel: Yeah.

Ann: And one of those layers is like what are you kind of doing and saying outwardly on social media? And one thing that I struggle with sometimes, especially in areas where I feel out of my depth or I'm feeling challenged, feeling like okay, I need to be in a place where I'm absorbing and learning and reading, I am not in a place where I need to be making statements right now, and particularly with regard to social media.

(19:44)

Rachel: Yeah. Well I think it's incredibly important for us all to assume a place of listening to people who are marginalized in the same way that it's imperative for me to listen to LGBTQ+ people, really hearing their expenses so I can understand it more. Listening to Native American experiences so I can really understand how I can continue to be an ally in the space I'm working in looking at race. It's imperative that white people, women in particular, are able to sit and listen because that sitting and that listening is what's going to lead to learning which will lead to you being able to take action that will be meaningful.

And so I think it's kind of two sides of the same coin that in order to be able to act as an ally I always say that empathy is the greatest way to get to the depths of that and the only way you can indulge in being able to say "Hey, I hear you, I see you, and I want to be able to support you in the way you know you need to be supported" is through sitting and listening and not letting your ego jump in. Not letting the defense mechanisms build a wall that doesn't allow you to really absorb what people are telling you. And I think people really need to start getting comfortable with the discomfort that comes with this kind of work because as we do say "Okay, I'm allowed to not feel my best in this moment in order to ensure that we all can feel better later on." And it really blows my mind that a lot of times the white women who interact with my page -- and I say white women specifically because I have a very large following that is about 98% white women and so that's kind of both my online interaction as well as the fact that I'm a black girl who grew up in suburban Ohio in a school of all-white students and I was one of the few black students, so this has been my existence and my understanding for a very long time.

(21:48)

But it really surprises me often that a lot of the white women that I interact with, they will really, truly think that being called in on their racism or being held accountable for their racist acts or their irrational thinking around race, they feel like that's the most offensive thing that can happen as opposed to the actual act they're doing against people of color. And so there's a lot of self-reflection that needs to happen. That also comes in the sitting and the listening. And then as you continue to do that you'll be able to make better choices in how you're able to be an ally once you have kind of that education and that intentional understanding of what those more marginalized groups, in this case black women, are telling you that they need.

Ann: What would you tell people who are like "Look, I am still in my place of discomfort and learning. I also feel this pressure to acknowledge an injustice has happened." What does it look like to do that? Do you expect that from people who are still working through it? In a really concrete way, I'm just curious.

Rachel: Yeah, I just think it's like this uplift of voices of the black women who are speaking. Repost what they've said. If you don't know exactly what to say on your own behalf say "Hey, listen to this black woman who's talking. What can we all learn from it? Listen to this person of color who's expressing their experience. I'm going to put this on my page in order for us all to see them and hear them and moving forward continue to do so." So there's going to be a lot of mistakes that are going to be made on everyone's part and I want it to be clear that, you know, your fear of making a mistake should never silence you from ensuring that you're trying to do the work. But I also think that there's never anything wrong with uplifting the voices of people of color, following them, listening to them, reading their work, sharing their work, and just letting people know that hey, I'm listening and learning and I want to hold my community accountable to listen and learn as well.

(23:50)

Ann: Definitely don't feel the need to answer this question with regard to making a recommendation to white feminists but I'm curious about the books that have shaped your thinking about this and the things that are really helping you and allowing you to find your power when you think about these really hard questions. Resources.

Rachel: I think that we really need to all re-check our heroes, who our heroes have been, and there are so many problematic people who we've been taught to regard. And so I'm learning -- my resources are often re-looking through history and seeing who the real heroes are. A lot of academic texts that I've been really enjoying specifically from Dr. Brittany Cooper, her book Beyond Respectability, has completely given me a renewed sense of the work that black women have been doing for so long and that's a really great book for people who are interested in where some of the foundations of black feminism have come from. And then of course a lot of the recent books on race that have been really shaping a lot of the conversation these days, the classics of bell hook, the classics of Mary Church Terrell, the classics of Anna Julia Cooper, Nikki Giovanni, all of the black women authors who have been putting down hard intellectual discourse around these topics, I think it's fair for us to go back and say where has this been happening over and over? What can we learn and continue walking on the shell that these women kind of paved the way for us?

Ann: Yes, absolutely. You know we love books over here. For listeners who want to engage more deeply with your work, find you online, all of that, how can they do that?

Rachel: Yeah, you can definitely find me on Instagram which is where I do most of my work on Instagram. It's @rachel.cargle. I also have a Patreon where I do some more in-depth things and you can find me at Rachel Cargle there as well. I'm currently touring my lecture Unpacking White Feminism and if you go on my website rachelcargle.com you can see my tour dates. I'll be all over the country having kind of really meaningful, in-depth discussions around the racist history of the feminist movement, what the modern manifestation of it looks like now, and how we can continue to work towards a more intersectional and inclusive feminism moving forward.

(26:20)

Ann: Ugh, yes. I also want to note for listeners that you've got a social syllabus and a bookshelf. You know, kind of pinned stories to your account.

Rachel: Yes.

Ann: So for I have to imagine ongoing resources that is a great stop.

Rachel: Definitely. The link tree on my Instagram profile has dozens of things, both work by me, other people, articles. I've written articles, article book suggestions, and like you said my social syllabus which is a collection of resources around various topics that is a really good thing to work through when you're first getting started in kind of this journey of understanding and being active around anti-racism.

Ann: Ugh, Rachel, thank you so much for being on the podcast.

Rachel: Thank you so much. I really, really appreciate it.

[Interview Ends]

Aminatou: This is so fascinating to hear and the way that you also setup the interview and when you talk about this kind of work as work, that labor feels different wherever you stand on the flavor spectrum as they would say.

Ann: I'm nodding heavily. I know you can't hear that through the microphone.

Aminatou: I don't know, it's just giving me a lot to think of about my feelings about how, yeah, how I feel that I do this work and whether it's like work that I want to do at all. You know, hearing her story all I can think about is wow, I don't even know why you bother to engage with these people because I am not surprised that white women are upset when black women ask for things, like basic minimum things, and yet I am always so heartened and so thankful and genuinely moved that black women do that. They do it for no recognition. They do it for no money. Rachel Cargle doesn't have a book that The New Yorker is reviewing like Robin DiAngelo. She doesn't have all these qualifiers or whatever. You know, and it's hard work and she does it. That's not a position I put myself in anymore because in my estimation I was like white people should talk to other people about race. Talk to me about the rent and about other things that I care about because it is deeply personal and it's also very painful honestly.

[Music and Ads]

(31:49)

Ann: I talked to Robin DiAngelo. Before we go to the interview I do want to read this little part of her book that talks about the fact that she is a white woman writing mainly to a white audience and I just -- I want to read the kind of . . . her thought process behind that choice. "In speaking as a white person to a primarily white audience I am yet again centering white people and the white voice. I have not found a way around this dilemma, for as an insider I can speak to the white experience in ways that may be harder to deny. So though I am centering the white voice I'm also using my insider status to challenge racism. To not use my position this way is to uphold racism and that is unacceptable. It is a both and that I must live with."

Aminatou: Whew, Ms. Robin shaking the table. [Laughs]

Ann: So I think I just wanted to read that also because I think that she -- I mean I did the interview with her. I am obviously also a white person.

Aminatou: [Gasps]

Ann: And so when we use terms in the interview -- I know, you'll be shocked to learn. When we use terms like we in the interview I think we are in dialogue as two white people and also her book is written as she says for a primarily white audience. And so I just want to acknowledge that so it does not feel dismissive or alienating to listeners who are not part of that we frankly.

Aminatou: Listen, I'm excited to hear you two in conversation because I'm 33. I don't think I've ever heard two white people alone talk about race so it is truly . . .

Ann: Oh my god, I talk to white people about race all the time.

Aminatou: Listen, I'm not there so I don't know. [Laughter] I don't know what you people do in your free time. I was excited for you to do the interview because that interview sounds differently coming from either of us. It feels like an eavesdropping kind of moment where I'm like what?

Ann: Yeah. And she'll -- you'll hear in the interview she makes the point that she and I, two white women with no one else around or as part of that dialogue, are having a racialized conversation because we are both people with a race. We are both people who are steeped in and experiencing whiteness. And so literally every time if you are a white person you look around the table or you look around the room you are in socially and you see only white people just remind yourself that you're having a racialized experience. That is one of many smart things she said but I will kick it to the interview now.

[Interview Starts]

Robin, thank you so much for being on Call Your Girlfriend.

Robin: Oh, thank you so much for having me.

(34:14)

Ann: I want to start off by asking what is white fragility? And I would love if you would also not just define it but talk about how you came to the definition and the experiences that led you to coin this term.

Robin: Yeah, it's a term that is meant to capture something that is apparently very, very familiar to many, many people and I think that's why it resonated so much. So it's meant to capture how often -- how defensive -- we white people are when our positions, our identities, or our advantages are questioned in any way. The fragile part of that term captures how easy it is to upset us, right? For a lot of white people the mere suggestion that being white has meaning, much less that you could know anything about me just because I'm white, that would set us off.

But it's not fragile at all in its impact, right? So as a white person I move through the world with a deep sense of belonging, relentlessly affirmed and validated. My image is reflected back to me virtually everywhere in every role. I come to feel entitled to that comfort. I come to feel entitled to be seen and responded to as a unique individual outside of my group.

At the same time there are many taboos about talking about race and a deeply internalized sense of superiority. I do not believe any white person grows up in this culture and does not know that it's better to be white. In fact the research shows that by age three to four everyone who grows up here knows it's better to be white. And yet I'm also told that to acknowledge that would make me a bad person. So all of this kind of makes this irrational stew inside of us and we just have never had to build our capacity to withstand the discomfort of any of that being challenged. And I think in large part being white means never having to bear witness to the pain of racism on people of color and rarely if ever being held accountable for the racist pain I have caused people of color.

(36:30)

So when that comes into question I lash back. It's a kind of unconscious seeking to regain my racial equilibrium, my racial comfort. But it's not fragile at all in its effectiveness. It's incredibly effective and I actually think that white fragility functions as a kind of everyday white racial bullying. We white people so often make it so miserable for people of color to talk to us about our inevitable and often unaware racist patterns and perspectives and most of the time they don't because they risk more punishment. They risk us bursting into tears and them becoming the aggressor and our hurt feelings and our anger and out withdrawal, our minimizing, our explaining. And so they endure it. And in that way it's a kind of everyday white racial control. And I want to be really clear that none of that has to be conscious but I'm less concerned with the intentions behind it than I am with the impact of it.

Ann: Yeah. I mean and it's interesting too, you know, thinking about some of these responses, I think about human beings often as just wanting to know what script to run. You know, it's like okay, my standard answer to any situation in which I might be confronted with my complicity in this big racist system is to say I don't see color or something that is already rapidly feeling outmoded. And so maybe people who are younger and progressive or feminist identified and who are white and who are listening to this are like "I know it's not the right thing to say I don't see color anymore, but what is the script I run now?" And I think it's so tempting, especially in the social media era, to default to okay, that's the wrong thing to say; what is the right thing to say? And I think we definitely, when we have hard conversations about race -- Amina and I on this podcast -- we get a lot of email that's like "Okay, what is the right thing to say?" And I feel like what you are identifying here is that is just the wrong question, like the right thing to say is just barking up the wrong tree altogether.

(38:45)

Robin: Oh I'm so glad you said that. It's a very disingenuous question. Okay, just tell me the right thing to say. What about your life has allowed you to be a full-functioning adult and not know what to do about racism? Why in 2018 is that your question? When people of color have been telling us for so long, when the information is everywhere? And really? One of the most simple things to break with the apathy of whiteness is go look it up. Take the initiative to look it up.

Ann: Do a Google as we like to say. Yeah. [Laughs]

Robin: Exactly. You know, that question is meant to be challenging. It's also sincere, right? Like really, take out a piece of paper and make a list. Why don't you know what to do about racism? And you will have your map. Because your first thing on there is probably "I wasn't educated." The second thing is "I don't have an integrated life." The third, "I don't talk about race with people of color or even white people." "I haven't cared enough to find out, to change any of that." As you can see nothing on that list is simple and all of it is complicated and takes an ongoing effort.

(39:55)

The other point you brought up is what I think of as default, right? Whenever I have a default response I'm not thinking strategically or critically, right? So, you know, I'm a cross-racial dialogue and I think oh, I'm just going to listen because I don't want to say the wrong thing. I'll just listen. That's you defaulting to quite frankly your most comfortable mode of engagement. You're not paying attention. You're not asking yourself in each moment what would be the best way to engage in order to move racial justice forward? And sometimes that is I need to listen, but in the next moment it might be okay, I need to show myself. I need to take a risk. I need to meet the people of color halfway who are taking risks.

And I'm not going to get that call right by everybody but that is the call I need to be trying to make. I need to be paying attention. I need to be holding my position as a white person, in other words really aware. And when I make a mistake in that then just hold that feedback and integrate it into the next time I'm struggling to make the determination. Do you see that difference between defaulting into just "I'll do this" versus really paying attention and thinking more strategically?

Ann: Right. Well the difference between "I'm just going to forever only listen and never be a participant" versus "I'm going to listen so that I'm better equipped to then put myself at some risk and enter this conversation" or do something that is action-oriented I think is a super-important distinction. And I'm really taking that to heart myself because I think that one of the messages that particularly white feminists often get is you need to listen to what women of color are saying. What should we be centering if we are centering them in this movement? And then the flip side of that is like but you can't just sit there in silence. [Laughs] You know? And so I think what you're really speaking to is again not defaulting to these kind of scripts I guess about what is the right thing to do.

(42:04)

Robin: You know, I wrote an article called Nothing to Add: The Role of White Silence in Cross-Racial Discussions. And I took on every rationale that people give including "I'm an introvert." Too bad, to be blunt. This requires something of us. This requires risk-taking and it can be scary. But what's the worst that's going to happen to you? Come on. Is that whatever degree of scariness equivalent to what's happening to people of color and the terrorism they live in on a daily basis from so much of our unconsciousness?

Ann: I want to talk about a metaphor that you use in the book that I love so much and I'm going to paraphrase it, I don't think you say it in exactly this succinct way, but essentially discomfort is a door.

Robin: Yeah, it is a potential door. When you do your best and take risks you'll make mistakes and that's where the deepest learning comes from. That's not a comfortable experience. So I often say when I'm in front of a group if I do a good job today in this talk the white people are not going to be comfortable the whole time. If you are either I did not do a good job -- I simply just upheld the status quo -- or you've got a pretty quick firewall that you need to look at. You know, that you've blocked out taking this in. Because racism is not comfortable and we definitely won't get there from a place of white comfort. And not to be comfortable is pretty much a choice for me as a white person.

So in those moments when you feel the discomfort the question is what will you do with it? It's an incredible door in, right? Like oh great, okay, I'm feeling completely unsettled. I'm feeling defensive. I'm even feeling resentful or angry. Why? How can that help reveal the meaning-making structure that I'm using to make sense of what you're saying? Use your reaction to figure out what you think racism is that you would have that response. And how is it functioning that you want to shut down right now, if you do? Who does it serve and what does it serve?

(44:20)

Ann: It's interesting because we talk a lot about friendship as a site of difficult political work or as a place where you can forge and affirm and kind of work out your values and find collective motivation for being better frankly or like living those things more authentically. And it's really interesting for me hearing you talk about that and something I've been thinking about while reading the book is for me I feel like I have had so many moments of revelatory discomfort as a result of my deep relationships with people who are not white. And it's a really interesting thing to kind of unpack the difference between just saying "Oh, I'm not racist because I have people of color in my life" which is not something I believe but it is something where I'm like oh, it is a strong motivator for me to do better by people that I love. Which is not to say that I wouldn't want to examine and work on these issues if I did not love people of color., you know? But there is an interesting thing to happen where not so much proximity but in the same way that thinking about patriarchy and sexism is a tool I will confess that often I'm like would I be able to look my friends who are not white in the eye and say "This is what I did in this situation?" And I will use that as a barometer sometimes. Which is, you know, probably levels of fucked up as well. I don't know. I'm curious about that, you know? And just in general your thoughts on friendship as a site of some of this work, if there's a potential for positivity rather than excuse-making.

(46:05)

Robin: Absolutely. I mean I think one of the kind of interruptions of segregation and the messages of segregation -- I mean most white people live segregated lives, and in particular from black people.

Ann: Right, like two-thirds I think or something of white people have no friends that are not white? Is that right? Two-thirds?

Robin: I think higher, about 75%. Or it's a very superficial my coworker kind of thing, right? And I want white people to understand that every moment you spend in white space is a deeply active moment of socialization. So white space is not racially-neutral, and that's another thing that a lot of white people seem to think. If you ask them kind of "How has your race shaped your life?" they'll tell a story about a friendship, a relationship, an action, a moment.

And again what that reveals is how deeply we think of race as what they have and if they're present or we're thinking and talking about them then those are racial moments. And we have this inability to think about whiteness or white space as racial moments but white space is teaming with race. Every moment that I'm in the white space I'm being reinforced in probably the most profound message of all and that is that there is no inherent loss to me.

Notice that white space tends to be termed good. If somebody tells me "Oh, this is a good school" I know it's a white school. If they tell me this is a good neighborhood versus a sketchy neighborhood I know it's a white neighborhood. Wow, what a message right? The absence of people of color is what makes that space good. Wow. And I got that message my entire life. It's deeply internalized within me.

(47:55)

So one of the most powerful ways that I have tried to counter that socialization is to build those relationships. So that's really key. And that doesn't free me of racism. It's better than not having relationships across race but it doesn't mean that I don't run into racism in my relationships. And so when I'm in front of a mixed group I'll often ask people of color "Do you have white people in your life who you love deeply and who on occasion reveal their racist world view to you? On occasion run a racist pattern at you?" And they all say "Yes, of course."

So we can't use it to again exempt ourselves. We can't use it as our evidence. But yes, it's one of the powerful actions we can take, right? And not in a using way. "Oh god, I need a black friend. Oh, there's one in my . . ." You know, it needs to be sincere and genuine and is probably going to come out of putting ourselves in situations that aren't necessarily comfortable to us. I think the other thing you said that resonated for me was the humanity then that you see, right? So I hear a joke or a comment and I see my beloved friend Debra's face and I've seen the pain on her face that joke or comment causes and I cannot participate anymore. I was not raised to see the humanity of people of color. I don't think white people are raised to see that. And so it's also a powerful contradiction to that, and like you I ask myself yeah, if Debra was standing here right now and she witnessed me being silent, oh god, right? I'm out of my integrity.

Ann: Right. Am I betraying the specific person I love?

Robin: Yes.

(49:45)

Ann: As opposed to the question of am I not doing right by some high-minded ideal? I think that that's kind of what I'm getting at.

Robin: Yeah. And I think we think it's all white people so it didn't hurt anybody to make the comment. And what I would say is oh, you just let white supremacy circulate in the culture. It did impact every single person who participated in it including you through your silence. You just participated in white solidarity. That impacts the society we're members of and the experiences that then people of color have when they interact with us. We have to understand it as active. People of color don't need to be present for that to be impacting us.

Ann: I think a lot of our conversation today has defaulted a little bit to a black/white false binary when talking about race and I would really love to hear you speak to the ways that white fragility plays out or in kind of explicitly viewing race for what it is which is not just like black or white. [Laughs] And how these issues are complicated or change when you really consider that.

Robin: Yeah, I actually don't think it's a false binary. I used to be really careful. You know, don't reinforce this black/white thing. But I am at a place after this many years of talking to white people there are book ends and white is on one end and black is on the other. I do believe in the white mind the ultimate racial other is black. I think about it as I was raised to be functionally illiterate on racism and part of gaining some literacy, and that's not finished, but part of that has been to understand both the collective kind of experience that people of color have through white supremacy but also the differences, right? What I've internalized about Asian heritage people is different than what I've internalized about say African heritage people. And even that umbrella, Asian, is part of the way that racism morphs right? Kind of collapsed this incredibly diverse groups. And they've been positioned differently in relation to whiteness.

(51:55)

And the closer you are along that spectrum between those two book ends, to one end or the other, that will shape your experience. There are certain groups of color that white people are more comfortable with. It does not mean they don't experience racism or that I don't need to understand how but white people are more comfortable with Asian heritage people -- heritage people -- in large part because of the racist stereotypes we have and how that also functions to further put black people down.

But there's a really hard question that Asian heritage people have to question themselves which is who have I aligned with? Have I aligned with whiteness or have I aligned with black folks? Where have I put my advocacy? And what does anti-blackness look like among my group? Because anti-blackness cuts across all groups of color, even black people. The darker you are the more compounded is the oppression.

So that's the way I think about it. I imagine some people will hear that as invalidating the racism other groups experience. I don't see it as invalidating it but I hope I've made clear why I'm comfortable talking about it the way I have.

Ann: And finally where can people find your work and all these resources?

Robin: Well the book is available from a range of sources. Of course you know indie book sellers I would always want you to go to first but certainly it's available on Amazon. If you go to my website robindiangelo.com, it's one word, and the DiAngelo is spelled D-I, and then under the tab publications are all of my articles. And just thank you so much.

Ann: Thank you so much for doing this. And last question I realized. Who are some of the other people who are doing this work and writing and thinking, particularly people of color, whose work you'd recommend? I'm sure it's on your website but I would love a few names shouted out as well.

(53:50)

Robin: Please look up Resmaa Menakem. My Grandmother's Hands: Healing From Racial Trauma. He's a black man, MSW -- you know, social worker -- and he specializes in racial trauma and this book is just beautifully written for all groups. He talks about white supremacy causes trauma in the white body also. And as you're reading he actually talks you through exercises like what's going on in your body right now? It's just a beautiful book. Carol Anderson's White Rage and also Ibram Kendi, also won the National Book Award, black scholar. Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. And then Ijeoma Oluo So You Want to Talk About Race.

Ann: Awesome. Robin thank you so much for taking all this time today.

Robin: Oh you're so welcome.

[Interview Ends]

Aminatou: Mmm, Ms. Robin, still shaking the table. [Laughs]

Ann: How did you feel about that part where she said "Just because you have a podcast co-host who is a woman of color doesn't absolve you?" I was like Robin, exactly.

Aminatou: I mean yeah, Ms. Robin gets it. It's also not a thing where okay, we did an episode about white fragility and it's over. Like white fragility affects my life every single day. It dictates a lot of the choices I make and how I feel about myself and how I'm allowed to deploy my own emotions. And so, you know, I just like -- it is not a one-off. It is also a very painful thing to talk about.

Ann: Yeah. And you mentioned the fact that Rachel Cargle does not have a best-selling book but she does have a lecture series called Unpacking White Feminism.

Aminatou: Everybody should pay to go to that.

Ann: I mean yeah, a herculean unpacking task. And she has all that info at rachelcargle.com, we'll link to it in the show notes. And Robin DiAngelo also has a ton of resources. You know we are such fans of reading in this family.

Aminatou: Reading saves lives.

(55:55)

Ann: Like things that are real 12-step, like literally lists of questions to ask yourselves. Like things that you should take out a piece of paper and write down your answers to to examine yourself, or questions you should maybe pose in the racialized space of your all-white friend group and talk about together if that happens to be your scenario.

Aminatou: While you were reporting this episode as they would say did you learn anything new?

Ann: Yeah, I think I . . . I have a personal -- like unpacking the strands between what do I do with my own channels of power essentially plus the task of listening and feeling like I'm not just hearing or clicking but truly taking in with the task of accountability and verbalizing. Like I think that balance of those things, the part of my conversation with Robin where she was talking about only listening not being enough and saying "I'm an introvert" not being acceptable, things like that are very easy . . .

Aminatou: When it comes to race I am an introvert.

Ann: I mean what white person isn't frankly.

Aminatou: I do not get my energy from you other people. Jesus. [Laughter]

Ann: And I definitely am guilty of this too, like worrying about is this the right thing to say at the right time? That's where I feel the real talk of what is the balance between all of those things? And the balance should always weigh heavier on speech and action I think is the takeaway.

Aminatou: I don't hear this kind of real talk from people who are not people of color so it's like it takes a moment to absorb. But yeah, I agree. I think that the place where people -- and the thing about it that's nuts is if you are not a man and you do not benefit from the privileges of patriarchy in that way you know somebody saying they're hearing you is very different than somebody doing something to support you. You already know that. So that's the framing that I always think. I was like somebody is always somebody else's white man so you need to figure out the ways you are doing that.

Ann: Sure.

(57:58)

Aminatou: But yeah, this is cool. I'm excited. I'm excited to keep talking about it.

Ann: Yeah, and I am also excited to keep talking about it. I have already given one copy of this book away to a friend and it's one of those books I will probably give away many times. It is an academic book and it's heavy on the real talk so therefore dense. There's an opportunity to examine yourself on literally every line if you're reading it as a white person. But I do recommend it and I recommend checking out the rest of the sources because you're right that this is not just a single episode.

Aminatou: You can find us many places on the Internet, on our website callyourgirlfriend.com, you can download the show anywhere you listen to your favs, or on Apple Podcasts where we would love it if you left us a review. You can email us at callyrgf@gmail.com. We're on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook at @callyrgf. You can even leave us a short and sweet voicemail at 714-681-2943. That's 714-681-CYGF. Our theme song is by Robyn, original music is composed by Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs, our logos are by Kenesha Sneed, our associate producer is Destry Maria Sibley. This podcast is produced by Gina Delvac.

Ann: See you in the resources section. [Laughs]

Aminatou: I know, see you on the resources section of the Internet.